|

|

||

|

Pro Tools

FILMFESTIVALS | 24/7 world wide coverageWelcome ! Enjoy the best of both worlds: Film & Festival News, exploring the best of the film festivals community. Launched in 1995, relentlessly connecting films to festivals, documenting and promoting festivals worldwide. Working on an upgrade soon. For collaboration, editorial contributions, or publicity, please send us an email here. User login |

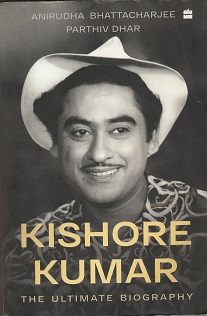

Kishore Kumar, The Ultimate Biography: The Penultimate Review

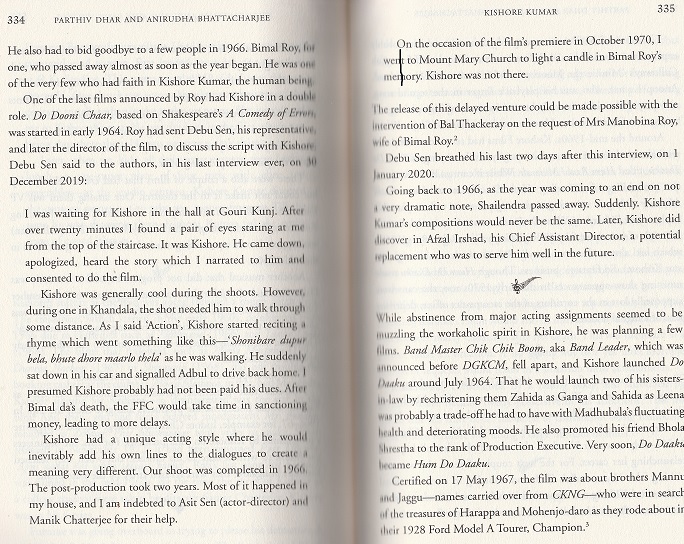

Kishore Kumar, The Ultimate Biography: The Penultimate Review Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Parthiv Dhar have been both adventurous and courageous in calling their Biography of that eccentric genius, Kishore Kumar, ‘The Ultimate’. Some biographies about one of India’s greatest ever playback singers-actors, also a music director and film producer, have already been written, and others will be written. And so, Ultimate is an indulgent word. Not given to such extravagance, I shall restrict myself to calling this review The Penultimate. Even that term sounds pompous when I think of the dozens of reviews the authors must have already received, and many more that will follow this appraisal. But it sounds nice, doesn’t it? “The penultimate review of the ultimate biography.” You would expect a biography of a public figure to be capacious, and capacious it is, at 592 pages. As many as 36 pages precede the book proper, and the text ends at page 468. The remaining pages are devoted to Notes, General Index, Songs index, etc. When you are writing about a personality like Kishore Kumar (KK), and calling it The Ultimate Biography, 464 pages seem insufficient. I do not think material must have been a constraint, judging by what is included. Probably publishers’ stipulation and the pricing factor would have come into play. Whatever the reason(s), you are left with a craving for more content, and more detail on some of the content. That is a plus, for some unquenched thirst is preferable to a satiated state. It is no exaggeration to say that the authors must have had access to ‘classified’ material, something like a diary, and consequently, it often reads like an autobiography, not a biography. The conviction with which ‘facts’ are put across leave little doubt that this is the case. But what do you do if you get hold of a ‘diary’, and are writing a biography of the man who maintained that diary? Do you publish the diary itself, warts and all, or do you choose segments and validate most of the chosen segments with a host of relatives and friends, while putting in relevant quotes from the diary, in toto? If you publish merely the diary, even in an edited version, you become the editor, not the author. Choosing to research and corroborate ‘facts’ means that you are burdened with the onerous task of editing the available material, picking out the interesting, even juicy, bits, and leaving out the undesirable and highly controversial ‘facts’ and ‘incidents’. In any case, an unedited diary can be both scandalous and boring. Though some untoward incidents and occasions are mentioned, there is nothing that shocks you or shows KK in very poor light. Naturally, you would not expect such content in a book that is meant to be a tribute, put together by two individuals who, in all probability, worship the phenomenon that was Kishore Kumar. Neither would you expect a person who writes a diary to jot down all his misdemeanors for posterity. To begin with, it would require extraordinary courage to chronicle all your own misdeeds. Coming to the biography, as formulated by Anirudha and Parthiv, does it mean that barring his occasional miserliness, mistakes, eccentricities, crankiness, moodiness and hoaxes, many of which are documented here, KK was a man without blemish? That is hardly likely, for any individual, barring saints. Literary figure and film producer Pritish Nandy has been chosen to write the Foreword. For many years now, his interview of KK, with KK on the cover, while Nandy was the editor of The Illustrated Weekly of India (now defunct), is considered the definitive one. In his Foreword, Nandy lauds KK for not bowing down to the powers during the Internal Emergency, which imposed a ban on the playing of all Kishore Kumar songs on All India Radio, Doordarshan (the only broadcast media in the country at that time) and in sponsored radio and TV programmes too. KK had been asked to participate in Geeton Bhari Sham (Song Filled Evening), which would consist of films eulogising the government’s 20-point programme. The communication was made in January 1976, at the height of the emergency. KK refused to play ball, as he did not want to be dictated to by the Minister for Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, acting, purportedly on the instructions of the son of the prime minister of the country. This is addressed in some detail in the book, but it ends in a sort of armistice, with KK signing a letter to the government, on 14 June 1976, “in a burst of spontaneity.” While I can confirm the ban, the blow by blow account can be read on pages 416-425. Going back to the Pritish Nandy interview, I remember Amit Kumar, KK’s son, telling me in a video interview conducted at his home shortly after KK’s passing away, that in the Illustrated Weekly interview, his father had taken Nandy “for a ride”, at least partly, in his characteristic prankster mode. There are many more things that Amit and Leena Chandavarkar Ganguly, KK’s widow and an actress in her own right, told me, but this is not the place to reproduce them. Let us move on to the Introduction, which follows the Foreword, and is written by Prince Rama Varma, Carnatic singer and veena artiste. He calls the book a labour of love by Parthiv and Anirudha. That it undoubtedly is. Among the scores of inputs that have found their way into the book, some come from Balaji Vittal. One recalls Balaji and Anirudha as co-authors of R.D. Burman: The Man, The Music, which won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema (2011). They also collaborated on S.D. Burman: The Prince Musician, Paperback (2022). Of the two authors of the book at hand, Anirudha lives in Kolkata while Parthiv is Guwahati-based, but has moved to Hyderabad a year ago. Putting the book together must have been a Herculean task, involving wide and frequent travel. It appears from various quotes that work on the tome started at least 12 years ago. As was to be expected in such a long journey, many of the persons interviewed or quoted have moved on to the hereafter. In the authors’ own preface, they mention a trip they made to Khandwa, KK’s home town, in December 2010. They also take this opportunity to indulge in a dash of hyperbole. A certain Ramnikbhai, a friend of KK, is quoted as saying, “Forget human beings, even wild animals would be spell-bound when he sang.” This is trumped by a quote from Filmfare, dated 29 February 2012, “Well, God created the Sun and Kishore Kumar. The rest of the creation was taken care of by minions. Hence there is only one Sun and one Kishore.” While few will dispute the talent of KK, such comments are over-the-top, to say the least, and do him no service. Wait! There is a six-page prologue before we get into the book proper. This is dedicated to the death of KK and how the news was broken to, or received by, a variety of people, beginning with Danny Denzongpa. Danny was to act in two films planned by Kishore Kumar but never completed. Amit Kumar, KK's elder son, was in Toronto at the time, in connection with stage shows, when the end came. The news naturally made it to Doordarshan’s evening bulletins, on 13 October 1987. KK’s death was indeed a national tragedy. And the preface then takes us into the book proper. Or, rather, Book I Bhairav: The Morning. Sections of the book are named after Hindustani Classical Music raags. This is a bit odd, considering that KK was not classically trained. One apocryphal story has him even swearing when told that the composition that he was called to sing was based on a particular raag. That he then proceeded to record one of his greatest songs ever is another matter.

Language used is largely aimed at graduate level readers, and even they, except for English Literature students, might have to check out the meanings of a few words. That is fine, and preferable to lowering of the literary bar. Pictures are aplenty, beginning with the one clicked by Tyeb Badshah to go with the Illustrated Weekly of India interview, on Page 2. So are illustrations, the first one appearing on Page 4. I was not impressed by the artist’s impressions, some of which were sketched without detail and others were redundant. However, the value of the photographs cannot be overstated. Almost all of them are nuggets to treasure. The cover captures the tragi-comic persona that KK, as projected in the early films that he produced. Sleeve and back-cover are also impressive. References to Binaca Geetmala, Ameen Sayani’s one-hour weekly film music hit-parade radio show, are found on eight pages, and naturally so. Singers, producers, directors, lyricists and music directors acknowledged it as the true measure of a song’s popularity. Songs sung by KK, as solos or duets, topped the annual rankings of Binaca Geetmala on six occasions, from 1953 to 1987. Kishore died in 1987. At 90, Ameen Sayani, who, early in his life, enjoyed very cordial relations with KK, has been gifted this book and will be reading it soon. To pen KK’s equation with classical music, the authors turned to Archisman Mozumder, Archie to his friends, and a hard-core, extremely knowledgeable music buff. Though KK had no formal education in classical music, many of his songs are based on raags and have been rendered as if he, indeed, knew them quite well. Of course, the credit has to be shared with the composer of the tune. After the advent of the audio-cassette era, in the late seventies, he used to insist that a recording of the song, usually in the composer’s voice, be sent to him well in advance, and he learnt the song playing the cassette over and over. It is common knowledge that KK venerated Kundan Lal Saigal and S.D. Burman, but not many might be aware that he revered music director Khemchand Prakash too. It was Khemchand (also known as Khemraj) who gave KK his first big break, and the death of Saigal and Khemraj hurt him a lot. As did the passing away of S.D. Burman, decades later. Ameen Sayani had been following-up with him for an interview for a sponsored radio programme, for months, and every time KK would give him the slip. But when SDB died, he agreed to make a recording in honour of Sachin Deb Burman, and gave an iconic radio interview. If I decide to dwell on KK’s songs and films, I will need another 463 pages at least. The book says he sang more than 3,000 songs. Some Hindustani film music statisticians insist that this figure is way off the mark, and he sang many more than 3,000. One fact that is documented in the book is KK’s aversion to wooing and romancing actresses, as an actor. He would to get the heebie-jeebies when asked to get lovey-dovey. That is news to me, and must be, to the lakhs of readers who will read this book. To write the Afterword, the authors invited KK’s step-daughter (his first wife Ruma’s daughter, from her second marriage), Sromona Chakraborty. Ruma spent the last 10-12 years of her life at KK’s house in Mumbai. Sromona writes, “He was certainly not mad. There was no streak of insanity in him whatsoever. Yes, like all great artist(e)s, he was moody.” How moody was he, will be revealed to every reader of this book. Or will it? And yes, you will learn all crucial facts about KK’s marriages, all four of them: Ruma Guha Thakurta, Madhubala, Yogita Bali and Leena Chandavarkar. The printer’s devil has crept in quite a few places, especially when Hindustani words have been transcribed in Roman script, but not so much as to jar. Example: Madhubala’s sister’s name is spelt Sahida when it should be Shahida. Published by Harper Collins, this easy to read paperback has a cover price of Rs. 699. On his hundreds of memorable songs, I will let them speak for, or rather, sing for, themselves. But I will mention only one that I really love, ‘Merey naena saavan bhaadon,’ (Mehbooba, 1976), and rest my case. Just as the length of any book is subject to constraints, so is a review. And after 2,048 words, it must fade out. Over to Parthiv Dhar and Anirudha Bhattacharjee, and their readers. 01.01.2023 | Siraj Syed's blog Cat. : All India Radio Ameen Sayani Amit Kumar Anirudha Bhattacharjee Archisman Mozumder Balaji Vittal Binaca Geetmala Danny Denzongpa Doordarshan Filmfare Geeton Bhari Sham Harper Collins Khemchand Prakash Khemraj Kundan Lal Saigal Leena Chandavarkar Madhubala Mehbooba Ministry of Information and Broadcasting Parthiv Dhar Pritish Nandy R.D. Burman Rama Varma Ramnikbhai Ruma Guha Thakurta Sachin Deb Burman Sromona Chakraborty The Illustrated Weekly of India Tyeb Badshah Yogita Bali Independent FILM

|

LinksThe Bulletin Board > The Bulletin Board Blog Following News Interview with EFM (Berlin) Director

Interview with IFTA Chairman (AFM)

Interview with Cannes Marche du Film Director

Filmfestivals.com dailies live coverage from > Live from India

Useful links for the indies: > Big files transfer

+ SUBSCRIBE to the weekly Newsletter Deals+ Special offers and discounts from filmfestivals.com Selected fun offers

> Bonus Casino

User imagesAbout Siraj Syed Syed Siraj Syed Siraj (Siraj Associates) Siraj Syed is a film-critic since 1970 and a Former President of the Freelance Film Journalists' Combine of India.He is the India Correspondent of FilmFestivals.com and a member of FIPRESCI, the international Federation of Film Critics, Munich, GermanySiraj Syed has contributed over 1,015 articles on cinema, international film festivals, conventions, exhibitions, etc., most recently, at IFFI (Goa), MIFF (Mumbai), MFF/MAMI (Mumbai) and CommunicAsia (Singapore). He often edits film festival daily bulletins.He is also an actor and a dubbing artiste. Further, he has been teaching media, acting and dubbing at over 30 institutes in India and Singapore, since 1984.View my profile Send me a message The EditorUser contributions |