|

|

||

|

Pro Tools

FILMFESTIVALS | 24/7 world wide coverageWelcome ! Enjoy the best of both worlds: Film & Festival News, exploring the best of the film festivals community. Launched in 1995, relentlessly connecting films to festivals, documenting and promoting festivals worldwide. Working on an upgrade soon. For collaboration, editorial contributions, or publicity, please send us an email here. User login |

Putuparri and the Rainmakers (2015); Interview with Director Nicole Ma

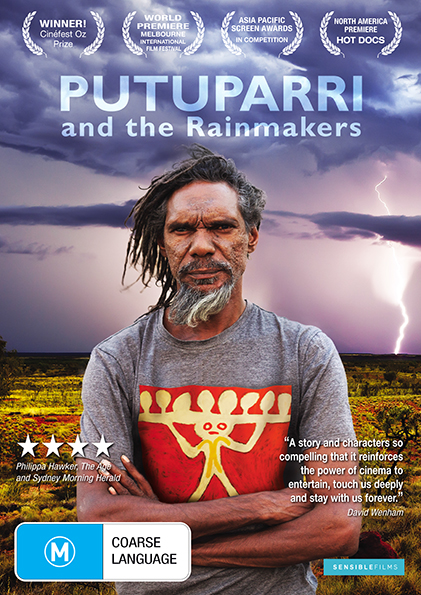

PUTUPARRI AND THE RAINMAKERS (2015) directed and produced by Nicole Ma, and produced by John Moore, held its world premiere at Melbourne International Film Festival and its Western Australian premiere at CinefestOZ in Busselton, Australia where the film won a first place film prize of $100,000 AUD. Starring Tom Lawford and Sylvester Rangie, the film is set in the Kimberly region of northwest Australia and tackles the issue of the nation's historical controversial conflict between colonial whites and colored indigenous people. The film follows one family in particular as they grapple with modern life while struggling to hold onto quickly fading age-old customs which define their cultural identity.

I recently interviewed director/producer Nicole Ma at her home in Melbourne. Here is what she had to say:

How did you meet Tom? NICOLE: I first went to Fitzroy Crossing in 2001 because I was making a documentary and I wanted to have an aboriginal component in it. When I pitched that film to the old people they weren't very impressed. Spider and Dolly, who are Tom’s grandparents and are featured in Putuparri, said “We're going back to our country and we haven't been there for years; we need someone to film it so you can do that instead.” I was curious because I'd never been in the desert so I went back to Melbourne and found the funding to go with them. On that first trip into the desert a lot of things happened that I didn't understand. In hindsight that first film I made it's quite superficial but it was the start of an on-going archive that eventually was used in this new film to help explain how the country has changed over time and how the rainmaking ceremony is evolving. It was on that trip that I met Tom and I found him quite intimidating at first. He didn't really talk to me much but at that stage the people I was close to were Spider and Dolly, the old people. Dolly took me under her wing and I felt that she wanted me to record their stories. Both Spider and Dolly’s passion is to pass traditional knowledge onto their young people. Dolly is a smart woman and she understood the value of film as a way of archiving their stories for future generations. When was it that you saw the rainmaking ceremony and then decided to make that the heart of your film? NICOLE: Over ten years I always thought I was going to make a film but I didn't know what form it was going to take. I didn't go in thinking “this is what I'm going to make” and I did not know that it would be about rainmaking for a long time. When I first met Tom he gave me a VHS tape. I didn’t bother to look at it as I had just been out to their country and filmed it with a great cinematographer so I was thinking: “I don't need bad VHS footage as I had just shot it.” I threw it in a drawer and forgot about it. About five or six years in, I thought “It's now or never I better start thinking about what story I want to tell.” In order to do that, I had to look at all the footage I had collected over the years. So that VHS tape was part of my research and when I looked at it I thought, “My god, that's the heart of the film! They're rainmakers!” It was priceless archival footage of old men doing a rainmaking ceremony at their sacred waterhole in the desert. The burning questions were would young people be able to take these traditions into the future and is there any point in knowing how to make rain. If you're a hunter and gatherer in the desert it's important to know how to make rain, but once you come into town, where water comes out of a tap, then what use is rainmaking really? What do you think the future holds for the aboriginal culture? NICOLE: I think the Kimberly is an interesting area for being able to hold onto the traditional culture, because it's quite remote. A lot of knowledge has been handed down to people like Tom and Buster (who in the film goes from a three year old to eighteen); particularly Buster because since he was born he has been by Spider’s side. The way forward is really up to them. I think they know they have a responsibility now because when they look at the film and they see all the old people in it, so many have passed away over the years, they feel they have to take it on. Aboriginal culture has a very complex skin system, which gives meaning to the networks of relationships. For example who can marry whom and who can do what within the community. For instance, in that rainmaking ceremony, Tom can't dig out the waterhole because within the skin system he is the father of the waterhole. It means he can only oversee what's going on and he can't actually do the digging work, whereas Buster has the right skin to do that work. In the future I think Tom is going to have to take on the responsibility of showing people how that ceremony works and in that way I think out of necessity things will change and evolve. I think both of them are pretty determined to keep their culture alive and strong. There's a lot of things going on that people just don't know about because it's not broadcast and it's what aboriginals call “sacred men’s and women's business.” As a filmmaker Tom has taught me to respect that there are some things that I will never know and I think that’s great. It means that the future for aboriginal culture is being protected and in good hands. It's incredible how much we can learn from these old customs, especially about how to work with the environment. NICOLE: Right, especially when it comes to taking care of the country and the reciprocal relationship between what the earth gives us and what we give back, which in our society we don't really give much thought. For us it is about taking what we can and the importance of the individual whereas the aboriginal culture is very much about the community and sharing and caring for each other and the country. What Putuparri is about is how that connection to country has been handed down and is so alive in the young people who have inherited it. For me, that's the most hopeful sign that things are going to be okay because they have so much they can teach us about caring for nature and the earth. It's very sad the way we are destroying the land just to make money without any thought for the future generations and the legacy they will be left with. Do you believe that ancient indigenous cultures know so much more about the land than modern civilization? NICOLE: Yes and I think this detachment we have to the land creates a spiritual void in us. One of the themes I was looking at was what people consider 'home'. The aboriginals can look at a painting and if it is about their country then that's home. They can stand on it and they believe they are standing on their home. They have a physical, spiritual and mental connection to home and it is embodied in paintings, dance and song, as well as the physical notion of ‘place.’ We, on the other hand, don't belong anywhere. We think we own our little piece of land and we will fight to the death to keep it. The boundary thing is very different too. We have no boundaries. We fight and take other people’s land. We fly around the world to different countries without that country even inviting us whereas to aboriginals it's inconceivable to go anywhere outside their country without being invited. That's why it's an honor for me to be invited to visit their country. They see that as a great gift. My aboriginal friends think Melbourne is my country so when they come here they expect me to take care of them and vice versa. That's the reciprocal relationship. You said you had a screening in Broom after you won the $100,000 AUD prize at CinefestOZ. How did they respond to that there? NICOLE: Oh they just loved it. When it won the prize at CinefestOZ, the news spread like wildfire around the Kimberly. I think they looked at it as a validation that people wanted to hear their story because in Australia we don't have a history of being interested in aboriginal culture. In fact, it has been buried and the aboriginals are trying to get it out but really the majority of Australians are not interested in their stories or their culture or the fact that they were the first people here. There's a very strong push not to understand the good parts of aboriginality whereas the bad parts are always in the news - the drinking, the family violence, the remote communities that certain people think should be closed - all those things are a path to genocide. It probably has to do with the fact that people came here and neglected to admit that there were aboriginal tribes living here. They were classed as fauna and the initial interaction between aboriginals and the invaders is a pretty sad and violent history. We never learned about aboriginal culture as it's not taught in schools. So, receiving the major prize at CinefestOz against I must say very stiff competition was very validating to the people of the Kimberley. When I finished the film I was a bit afraid the community would not like the negative aspects in the film, the violence and drinking, but they felt it was the truth and they said, “Look, you've shown the truth and you've shown the beauty of our culture as well. This is really a blip in our continuum because we've been here 40,000 years and all this has happened in the last 200 years.” How have Australian audiences in general reacted to the film? NICOLE: I've been quite astonished by the emotional response to the film. I think one of the reasons is that the film doesn't play the guilt card. It’s not polemic, it’s a personal story of an aboriginal man who lives in a remote community in Western Australia. It shows his struggle to live in two worlds and by hearing his story the audience gets to see what it is like to be in his shoes. It's very much an observational documentary. I am shocked when audience come up and say to me, “I didn't know that happened or I didn't know about that.” There's no curiosity here for the aboriginal culture; and yet, if you go out of Australia that's the first thing people want to know, the first question usually is about what's going on with our aboriginal population. I am surprised by the lack of integration in Australian cities. Why is that? NICOLE: Australia was pretty well populated with aboriginal tribes when the Europeans first arrived. Most of the coastal cities have hidden stories of massacres and genocide. The local tribes were nearly wiped out. It’s only in northern Australia due to it’s remoteness that the culture survived. That's one of the reasons I decided to make the film, because I was living in the city and had never met an aboriginal. I knew nothing about their culture and I had no curiosity, I'm ashamed to say, until I went there. And when I went there I felt really at home. They made me feel part of the family. When they took me to their country, I thought “We seem to have got it all wrong here.” The story I was seeing was much more complex than what we were fed in the media. I kept returning over the years and realized I was having an amazing experience of getting to know aboriginals. I wanted an audience to experience what I was experiencing. So I chose to focus on one person and their family so the audience could really get to know them, get to know their life, their history and the social context they have had to navigate in trying to keep their culture going while also having to live in our world. A lot of them can't read or write and yet they're really smart about how they use our system. Now that the film has finished and has won this prize, what is next for them? NICOLE: Dolly wanted to have a big party in Fitzroy Crossing, but she fell and broke her hip so she missed the party. But now she is better we might have to do that again. She recently won the major indigenous art prize in Australia for a painting about her country so she feels she has a lot to celebrate. Dolly is good now and Spider is still going but they are both getting old. They are ready to pass the baton and it’s really up to Tom to take up the reins. I think the film and the experience of speaking about it has made him aware or provided a platform for him to talk about the way forward. I can see him thinking about what he needs to say to people because Australians are asking him, “Well, what can we do?” because they feel helpless. A lot of people either feel guilty or don't care; there's nothing in between. So Tom says to the audience, “You know, you white fellas, you're here. There's nothing we can do. We don't like it but you're here and what we need to do is move forward from that. We're brothers and sisters and we need to walk together now.” He gives the audience some hope of how we can shift the situation instead of it being us and them.      Interview conducted by Vanessa McMahon Visit the official site here: http://putuparriandtherainmakers.com/ 03.10.2015 | CinefestOZ Film Festival's blog Cat. : PUTUPARRI AND THE RAINMAKERS (2015); Interview with Director Nicole Ma Interviews

|

LinksThe Bulletin Board > The Bulletin Board Blog Following News Interview with IFTA Chairman (AFM)

Interview with Cannes Marche du Film Director

Filmfestivals.com dailies live coverage from > Live from India

Useful links for the indies: > Big files transfer

+ SUBSCRIBE to the weekly Newsletter Deals+ Special offers and discounts from filmfestivals.com Selected fun offers

> Bonus Casino

User imagesAbout CinefestOZ Film FestivalThe EditorUser contributions |