|

|

||

|

Pro Tools

FILMFESTIVALS | 24/7 world wide coverageWelcome ! Enjoy the best of both worlds: Film & Festival News, exploring the best of the film festivals community. Launched in 1995, relentlessly connecting films to festivals, documenting and promoting festivals worldwide. Working on an upgrade soon. For collaboration, editorial contributions, or publicity, please send us an email here. User login |

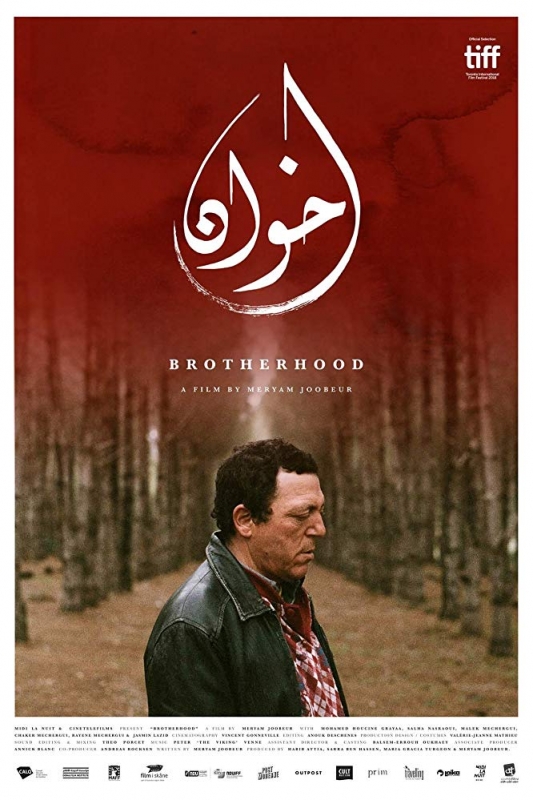

Extremism, family conflict and betrayal collide in Meryam Joobeur's new film

Meryam Joobeur is a young Montreal-based filmmaker who has worked with Sasha Lane of American Honey fame, among others. Her new short film Brotherhood explores issues of cultural dislocation, family tension and sacrifice. It won the award for best Canadian short film at TIFF in September. In Brotherhood, a family’s eldest son returns home from Syria to his Tunisian shepherd family, accompanied by his new wife - a young woman wearing a niqab, a garment in which only the eyes are visible. This creates immediate friction with his family, especially his father. The unresolved issues in his relationship with his son find expression through suspicion of this strange woman and her unknown habits. He doesn’t want his two younger sons to grow up thinking this behaviour is normal, and his suspicion starts to boil over, leading ultimately to a final betrayal. “It’s interesting for me to explore how the families feel when their child does something this extreme,” Joobeur said. As I watched the film I asked myself how many times this situation was playing out all over the Middle East. How would a family who may have driven their child into the arms of the Islamic State react if and when that child returned? And how would they reconcile with the fact that what may have seemed like a family quarrel in the heat of the moment could have been the defining moment in their child’s decision to irrevocably turn their back on what they knew? And how would Canadian audiences react to a film portraying the domestic side of a long-running conflict that most of us only ever see through the lens of politics? The core of the 25-minute Arabic-language short revolves around the father Mohamed (played by Tunisian TV actor Mohamed Hocine Grayaa). His son has taken up arms with religious fundamentalists who see the world in stark black and white terms, but ironically he is something of a fundamentalist himself. “I think Mohamed has a very strong sense of right and wrong,” Joobeur explained. “He has a clear vision of how life should be.” “I structured the film like an onion with different layers, and those layers are Mohamed’s perception of the situation.” The focus for all of Mohamed’s suspicions turns out to be his daughter-in-law’s niqab. He cannot know much about her, and for him this is deeply disturbing. “For Mohamed the niqab is really the embodiment of everything he hates,” Joobeur explained. When Reem removes the veil and is revealed to be a teenager, “he creates this image that his son is a predator.” Brotherhood was shot on location in Tunisia with a small crew. The hills, dunes and brush of the tranquil desert landscape give the film a look that is both meditative and apocalyptic. Winds whistle in the distance and goats calls out. The project, Joobeur explained, actually came about by accident when cinematographer Vincent Gonneville was looking for places to shoot a different project. He reached a small shepherding village, where he stumbled across two young brothers (the two younger siblings of the film), instantly recognizable thanks to their freckles and bright red hair. “We found these boys by chance in the town…and the whole trajectory of what I wanted to do just completely shifted. So I let go of the other project and focused on this.” The Montreal-based crew flew to Tunisia soon after, first to retrace their steps and find the tiny hamlet where they saw the boys - which fortunately they did - and then to begin preparing. The parents were played by professionals, but the three brothers and Reem were non-actors. “I was really nervous about having to train nonprofessionals, but I have to give it to all of them - they have a natural talent,” she recalled. The niqab retains its power to shock and to polarize, whether you come down on the side of those who believe it should be tolerated, or its detractors. It is a visual manifestation of uncompromising belief, regardless of why the wearer dons it. “[Mohamed] just can’t stop looking at it,” she said. The niqab is another way that the film addresses the larger ramifications of the Syrian conflict, as instability and hardline religious positions (of which the niqab is one of the most visible) Malek doesn’t preach extremism to his family - instead, his wife, who is Syrian, is using the garment to hide herself. Joobeur visits her family in Tunisia regularly, and since the 2011 revolution she has noticed more niqabs in public, when before they were unknown. Joobeur also related a story from a friend who attended a screening. During the scene where Reem the wife removes her niqab at her husband’s urging, revealing to the family just how young she is, a man sitting next to her gave vent to an unexpected prejudice. He said out loud “Now [Mohamed]’s probably going to rape her,” Joobeur recalled. “I was a little surprised, and – well – I was hurt. Nothing in the film sets this up. But then I reflected it on a bit and realized he’s probably bringing his own stereotypes of Arab men and Arab culture into the viewing process. Then I thought about it and [realized] he is the right person to watch this film, because that assumption will be broken by the end. So that was a really interesting realizaztion I had about audience engagement and what an audience brings to the viewing experience. And how important it is to make films that break that perception.” As the Syrian conflict winds down, situations such as these depicted in the film will only become more common. Tunisia sent more foreign fighters to Syria than any other country, although Joobeur stressed that the village of Louka, where the film was shot, did not have any problems with extremism, and the family didn’t know anyone who’d gone to Syria. At festivals, short film screenings seldom draw as big a crowd as feature length, but the screening was well attended with audience members asking insightful questions, she said. Joobeur is currently working on a script for a feature-length version of Brotherhood, which she hopes to have ready in time for winter. For now, she’s content to get some rest and [thank her lucky stars] for how lucky she was with this project. "Everything just went so smoothly with the film, it just kind of came together. I don’t know if that will happen with another project again.”

BROTHERHOOD, dir Meryam Joobeur, 25 mins, Arabic (s/t) Prod. Meryam Joobeur, Midi La Nuit, Cinétéléfilm Starring Mohammed Houcine Grayaa, Malek Mechergui, Salha Nasraoui

02.10.2018 | Tom Llewellin's blog Cat. : arabic canada film Interview middleeast tiff toronto tunisia Independent FILM

|

LinksThe Bulletin Board > The Bulletin Board Blog Following News Interview with IFTA Chairman (AFM)

Interview with Cannes Marche du Film Director

Filmfestivals.com dailies live coverage from > Live from India

Useful links for the indies: > Big files transfer

+ SUBSCRIBE to the weekly Newsletter Deals+ Special offers and discounts from filmfestivals.com Selected fun offers

> Bonus Casino

About Tom LlewellinThe EditorUser contributions |